Home » Literature Archives » The Monocled Mandala

THE MONOCLED MANDALA

by Yin Shan Shakya

It was ten o'clock in the morning and I was already late opening up. I worked fast, but efficiently. If there was one thing I had going for me it was that I could do my routine with second-nature certainty. I went into the little den-like shop and turned on the lights to see what, if anything, had somehow managed to escape its temporary home. Everything was calm. Nothing had emerged from the darkness, and so I proceeded to the back room to prep the water and food supplies needed for all the reptiles and amphibians.

We were a little shop that dealt mostly in snakes, but we were a herpetologist's dream. We had everything from White-lipped Tree Frogs (Litoria infrafrenata) and Red Legged Tarantulas (Brachypelmasmithi) to Panther Chameleons (Chamaeleo paradis) and the most striking Brazilian Rainbow Boas (Epicrates cenchria). And it was my job to keep them healthy and to create an atmosphere conducive for these animals to breed in captivity.

My interest went beyond the commercial aspects of the shop. We also kept a less popular group of snakes, the Elapids, and one particular species of these extraordinary snakes fascinated me. I was literally entranced by the Monocled Cobra, (Naja naja kaouthia).

Elapids consist of a large family of venomous snakes that are circumglobal in distribution and are characterized by the presence of fixed, venom conducting hollow teeth, or fangs, positioned in the front of the mouth. These snakes have been important characters in religious folklore dating all the way back to the beginning of Asia's ancient cultures. But of them all, the one that is most amazing is the Monocled Cobra.

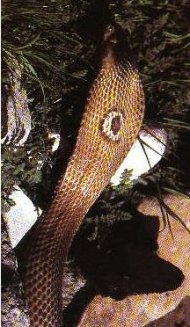

I first learned about the Monocled Cobra from Buddhist stories that originated in India and were then passed orally into the folklore of Japan and China. I had been studying snakes for years, but this great naga was special to me. Once, while thumbing through a large, glossy book of snakes, I found a picture of the snake and was struck by this timid and elusive creature's hood. I blew up this picture and posted it on my wall just to see the ocellus located on the back of the head of the outstretched hood. It's truly amazing to see. This particular ocellus looked identical to the Japanese enso (the Circle of Infinity), although the design on the hood may range from a circle to a horseshoe shaped pattern.

This picture kept drawing me into the great Zen mystery of Infinity's Circle and all its representations of simplicity; beginnings; endings; emptiness with fullness; all things visible; and all things unseen - all at once. It is the beginning and ending of all life, the circle of life.

Now, I was running late and even though I had my routine down to machinelike efficiency; the allure of that Monocled Cobra stopped me in my tracks. I stopped what I was doing and sat in front of the glass staring into its flared hood. I did not even notice that a customer had come into the shop; and I as I was staring at the Cobra, he was staring at me. "Man!" he said, rousing me, "You were really in a zone." I laughed.

I explained the fascination of the design on the hood, but he didn't understand. "It's not just the circle," I said. "It's more. It's the element of danger that accompanies the message. Spiral and circular shapes have a fascination independent of what they are inscribed on; but that danger element increases the intensity of the fascination. It's arresting, I guess." He still didn't get it. Then I remembered the old Zen mondo and told it to him:

Once, a warlord who was traveling with his army, stopped by a monastery to visit his old Zen master. While the two of them were talking quietly over tea, a monk outside their window was babbling on incessantly about his inability to concentrate. His complaints began to irritate the warlord. "Master, " he said, "Would you give me your permission to solve this monk's problem?" The master agreed.

The warlord called the monk inside and poured a cup of tea, filling it to the brim. "I will help you to learn to concentrate," he said. "Take this cup of tea and carry it around the periphery of the courtyard." Then he summoned six of his archers.

As the monk casually picked up the tea, the warlord turned to his archers. "Follow him!" he said gruffly, "and if he spills a single drop, shoot him." And on that day the monk learned to concentrate.

My customer finally understood. Concentration does not have to be fleeting; If we are truly motivated we can command our attention to stay exactly where we want it to stay. The circle accommodates a point of fixation. It draws us into itself and its many meanings go around and around our mind like a slowly spinning wheel. We wind our thoughts onto its periphery, and in the center we can see beyond ourselves.

Urgency and danger add depth to our concentration. A greater value is placed on our ability to fix our attention on the essentials, to let all the unnecessary thoughts fall away. We achieve one-pointed concentration because any division of our focus could be fatal. I could see the monk slowly walking around the courtyard, his eyes glued to cup's amber circle, the archers' eyes focussed on him the way the cobra's eyes focussed on its prey.

For years, as it had been that morning, the cobra's ocellus was my enso which I used to see past myself and into Zen's Empty Circle. It was a good way to begin the day.