Home » Literature Archives » Cultivating the poise of a dead man

THE BOOK OF THE SAMURAI

Part 10: Cultivating the Poise of a Dead Man

by Ming Zhen Shakya

In Chapter 10, verse 11, we read yet another reference to death - a word which in The Hagakure references as many different states of being as it does in purely spiritual literature.

"A certain person said, 'In the Saint's mausoleum there is a poem that goes:

If in one's heart,

He follows the path of sincerity,

Though he does not pray,

Will not the gods protect him?

What is this path of sincerity?"

"A man answered him by saying, 'You seem to like poetry. I will answer you with a poem.

As everything in this world is but a sham,

Death is the only sincerity.

It is said that becoming as a dead man in one's daily living is the following of the path of sincerity."

In William Scott Wilson's footnote, we learn that the saint to whom the Hagakure refers is Sugawara no Michizane (845-903), a government official who achieved fame as a poet, scholar, and calligrapher. Exiled from the capital, he continued to write; and upon his death was apotheosized as the patron god of literature.

The poem poses the question: If someone isn't religious but has lived his life intending always to follow the Good Way, does he still qualify for heaven's aegis? Further clarification is sought: "What is the Good Way?" The response indicates that since religious formalities and good intentions are part of the world of illusion, only the exit from illusion can be a Good Way.

The opening lines of Verse 10:11's poem pose a question that is often answered at funeral services. Whenever someone who is not religious dies, a friend or relative who is religious will try to excuse the deceased's lack of support for the church by offering a reassuring endorsement: "He was a such good man at heart that God will surely overlook his lack of devotion and will welcome him into heaven." This comforts all who fear that the services are dispatching a devil heavenwards.

How do we ever know what anyone is "at heart"? The closing lines dispel the notion that such determinations can ever be valid. It is in the world of illusion that such judgments about good and evil are made. Essential Truth, Honesty, and Sincerity are found only in the Real world, and only by being "dead" to the world of illusion, can we find the way to appreciate such qualities.

The "dead man" model for living in the illusionary world has particular appeal to both martial artists and to those of us who follow the teachings of Hsu Yun. I'll digress a bit:

In 1985 I visited Nan Hua Temple at Ts'ao Chi, thirty kilometers or so outside Shao Guan, in Guang Dong Province, China. The temple was different in those early days of its post-Cultural Revolution revival. Only a dirt road led from the city out to the temple, the gates of which were large sagging wooden doors that scraped the dirt as they were pulled open and shut.

I spent several days at an inn adjacent to the complex, and then Nan Hua's Abbot invited me to stay in the monastery, in a small, two room reception building - a building that was closest to the entrance.

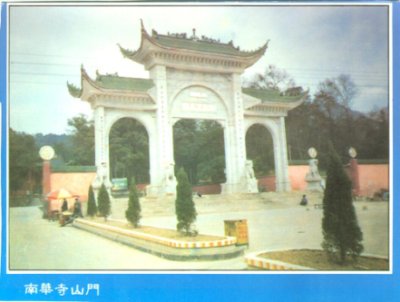

The New Gates of Nan Hua Temple (Official Monastery photo)

Inside the entrance gates was the usual Daoist shrine, Southern School Zen's acknowledgment of the debt it owes Daoism. The local Daoists would come every day to set off firecrackers at the shrine, a devotion they performed so diligently that the air around the shrine the air was thick with smoke and the ground was five inches deep in shreds of red fire-cracker paper. Kids shuffled through the paper as they'd shuffle through piles of autumn leaves. The noise was an irritating staccato that continued throughout the daylight hours. (A few years later, by government order, the practice was mercifully discontinued.)

But at dusk, all was wonderfully quiet, and from the bedroom I could hear the gentle ticking of a pendulum clock in the adjacent meeting room. The sound was hypnotically beautiful. (I had learned to meditate by focussing on an old clock's ticking.) I mentioned this to one of the older nuns who told me that Hsu Yun was fond of that sound, too, and often told his disciples that they should strive to be like a clock that in fair weather or foul maintained the same cadence. "''Even in a thunderstorm, the clock does not change its rhythm,''" she quoted him as saying. "That's why," she added, "he advised everyone to cultivate the poise of a dead man." Verse 10:11 of the Hagakure addresses this.

As Heraclitus famously noted, "All things are in flux." By "things" he meant the material, samsaric world, the world that the poem calls "sham." Zen defines Reality as true, immutable, universal, eternal, and unconditional. These are attributes of Nirvana. Their opposites constitute the samsaric world that we consciously apprehend - keeping in mind that the mind and the senses with which we apprehend this samsaric world are themselves conditional, parochial, fleeting, and subject to revision. The ego-conscious mind, therefore, is part of the illusionary, "sham" world.

Both Zen and the martial arts abound with such expressions as "Dying to self"; "Killing the fool"; "You can't kill a dead man"; and so on. We know that the intended victim is the ego - that judgmental faculty that always manages to give itself high marks for honesty and good intentions and imagines that, in one way or another, it will live forever.

The question then becomes, "How do we kill our own ego?"

In the world of illusion, we have no trouble destroying other people's egos. We nag, insult, ignore, reject, gossip, betray, and break promises as easily as we make them. Understandably, we are reluctant to turn this venom on ourselves. Besides, like most venomous creatures, we are immune to our own poison. We have to find another approach.

What is it about a dead man that we're trying to emulate? It cannot be the loss of a conscious mind and senses. (We need them if we intend to function in the material world.) It is his absence of emotion. A dead man neither loves nor hates, is neither calm nor angry, and is definitely not moody. He does not feel compelled to judge the nature and quality of the people, places, and things he encounters.

Again, the dead man does not respond emotionally to his environment. It is not that he has no pulse, it is that his pulse does not change.

Behind desire and aversion is the hidden dynamic of fear. Usually we can easily identify our likes and dislikes, but the fear of failing to get what we want; of losing it once we have gotten it; of missing an opportunity even to compete; or, worse, of being the victim of someone else's manipulations are difficult to pinpoint. They are the nebulous stuff of anxiety.

The martial arts' training regimen removes two important kinds of fear: The first is physical. The student experiences all the great and reasonable fears - of failing; being hurt; being ridiculed by onlookers; of disappointing his teacher; and so on. These fears will attenuate as he is guided through a series of progressively more demanding exercises. With each success, his self-confidence increases as his fear diminishes.

Since fear responds well to a "cry wolf" scenario, it can be eliminated by the experience of confrontation. Before any new and dangerous undertaking, a person will feel fear; but when no harm results from the encounter, the fear of it diminishes. And just as the veteran Samurai continues to train to maintain his level of skill and agility, he also disciplines himself to consider all possible ways that he might die in battle. Rehearsing each of these ways in his mind yields that "familiarity which breeds contempt," a casual appraisal of even the most unlikely means of destruction. It also suggests to him which skills he should practice so as to survive these possibilities.

Fear inhibits constructive thought and slows response time. Only when a warrior is unafraid can he perform with spontaneous proficiency.

The second kind of fear naturally occurs whenever a person becomes attached to someone or something in his environment. He fears losing something he values, something with which he identifies himself. In the illusionary world, the qualities of a possession magically adhere to the possessor - ("I own a better house than you; therefore, I am a better person than you.") These are the weighty oppositions to the dead man's' poise.

In Jungian terms, attachment begins with fascination, curiosity, interest. And then the attractive feature of the "object of interest" enlarges into a screen upon which one of the various archetypes that prowl the restless psyche can project itself. The "e" in emotion means "away from" and "motion" is moving. Like a film image reflecting on a silver screen, the archetype projects itself away from the person and onto the object of fascination. This is the connection that must be severed.

Regardless of whether the targeted recipient is loved or hated, an emotional bond prejudices choice and fosters psychological conflict. For the same reason that a surgeon does not operate upon his own child or a lawyer does not defend himself in a criminal case, the Samurai does not fight when he is emotionally involved in the contest. To kill in anger is to kill in an emotional state - which indicates that the one who kills is attached to his enemy by an relationship that has prejudiced his actions and will disturb his mind afterwards. It is as unbecoming to gloat about having killed a man as it is to regret it. The man's life must mean absolutely nothing to him. If duty requires its destruction, he destroys it.

An emotional response of love or hate is the certain indication that he has compromised his judgment and can no longer act in an unprejudiced manner. And from the moment he first feels that emotion, he will try to get physically close to the person or object, to limit its movements, and to exercise some degree of control over it. In a very real sense, it is the object that controls him.

How does the samurai "detach" himself from the bonds of the sham world?

In these maladies of the heart, "An ounce of prevention is truly worth a pound of cure." At the initial moment of feeling a fascination with a person or object, the samurai can discipline himself to turn away and not pursue it. He must deal in reality and not in the day-dream fascinations of fiction. To help himself resist any temptations, he pointedly recalls the unfortunate outcomes of previous liaisons that went awry. He may actually list them as an exercise. He also recalls instances of emotional extravagance - anger or infatuation - which were hot and noisy and came to nothing but the waste of time and energy. He recollects those persons and things he greatly valued and whose names now he can barely remember.

If he incurs the contempt of another, and he is chastised, insulted, lied about, betrayed, or rejected, he steadies himself, and tries objectively to understand how his critics might have arrived at this unfortunate misreading of fact. He doesn't silently seethe about it and scheme to get revenge. When he is certain that he is not acting emotionally and believes that the situation requires correction, he takes action.

Should he ever be hooked by love or hate, detachment is a difficult problem. Much depends on the nature of the attachment and the strength of his religious faith: Freeing himself usually requires discipline, prayer, and geographical separation - the old "grand tour" therapy of prolonged diversion. He can "wait it out," passively letting the attraction or revulsion diminish of its own accord - emotions feed on novelty, and when no provocative actions are taken, the relationship slowly starves. He can trust that the odds are with him - that the object of his affection or loathing will turn out to be substantially different from what he, she, or it first appeared to be. Other persons may interfere in the relationship and destroy the pleasure or pain derived from it. The discovery that his enemy has acted kindly towards him may dissolve the enmity, as also the discovery of his lover's infidelity may bring a painful and abrupt end to the relationship, leaving only a bitter residue that will turn to dust with time. Once the bond has been broken and the archetype safely withdrawn, the samurai may be wise enough to guard against future projections. He will cease trying to determine good and evil. Evil is the hell of never escaping the material world. Good is found only "through the looking glass" - in the reverse of the material world - the exquisite transcendental spiritual experiences which begin with the true meditative state.

Any particular enjoyments a warrior indulgences in... music, foods. hot baths, and so on, can be drained of their seductive qualities by rigorous "sensory" (pratyahara) exercises such as are found in any yoga or zen program, or cultivating a Spartan attitude. Once they lose their hold on his desires, he will not differentiate between a hot and a cold bath. The duty is to clean himself, not to luxuriate in a tub. If a hot bath is offered him, he is free to enjoy it. He is not free to manipulate his social environment in order to obtain it.

The man who cultivates the poise of a dead man regards the people, places, and things of the material world as worthy of attention - but not worthy of emotions. When he commits himself to a course of action, he does his best to achieve it. But he accepts success or failure with the same natural restraint. He strives to live honorably, without guile, i.e., to be genuine - to be internally as he appears to be externally. In a word... sincere.