Home » Literature Archives » Gilding The Lily

GILDING THE LILY

On the tenth anniversary of Empty Cloud: The Teachings of Xu Yun.

by Ming Zhen Shakya

Keith Mars, employer and father of TV's winsome sleuth Veronica Mars, knows how easily an attempt to gild a lily of truth can damage the flower

A client claims that he is being cruelly harassed; and after an initial investigation, Mars determines that there is, indeed, convincing evidence to support the claim. The client, however, is not content to let the existing facts speak for themselves; and so he fabricates additional evidence, "proof" that he thinks will both strengthen his case and cast suspicion upon the person he believes is guilty. He plants a few incriminating objects for the detective to find; but Mars is not easily fooled. Unfortunately, once he has uncovered the trickery, he must inform his client that he can no longer be a beneficial witness for him. To "tell the whole truth" would require that he disclose the client's deception; and when one instance of falsified evidence is admitted, even genuine evidence becomes tainted.

Just so, the saintliness of such a person as Hsu Yun is amply supported by the existing evidence. But as if the truth were not enough to sustain this claim to holiness, people, without malice but with the kind of "boosterism" that thrives upon exaggeration, find it necessary to enhance his image, to embellish it beyond that natural astonishment we find in considering such a man as he.

Until ten years ago, in English, there were only two sources of information about this most revered of Chan Buddhist saints. Both works were translations effected by Mr. Charles Luk (Lu Kuan Yu) who was not, unfortunately, a native English speaker. Subsequent revisions of his work have had to be made. One of his original translations was that of Mr. Cen Xu Lu's redaction of Hsu Yun's personal memoirs, which included the editor's account of Hsu Yun's death; and the other was Luk's translation of notes compiled during a series of lectures Hsu Yun gave in Shanghai in 1952. Neither source has done Hsu Yun justice.

The autobiographical text was corrupted with hagiographic ga-ga that morphed into a first-person narrative. The first and most objectionable of this Lily-Gilding was the extension of his life by twenty years. Accordingly, Hsu Yun, a malaria victim, was said to have been born in 1839 and died in 1959. To us this unlikely 120 year life span, asserted so emphatically and with such pointless pride, is problematic. (The life expectancy in China in 1949 was 35 years.)

Cen Xue Lu, who had already edited the Annals of Yun Men Temple, appreciated the Chinese reverence for Hsu Yun. In the decade following the Civil War, China was in turmoil; and, as he edited the Memoirs, Cen surely understood how important it was to the people to retain their faith in this "proof" of Hsu Yun's protective sainthood.

But in times of prosperity, folk beliefs give way to more sophisticated appraisals. Improbable assertions not only lose their ability to inspire; they often become inimical to the inspirational process. Besides common sense, there are good reasons to suppose that his birth date of 1839 should have been 1859, a crucial twenty year difference.

In fact, historians who attempt to document the lives of religious figures often have great difficulty in penetrating this strange twenty year barrier. It is a common religious practice to regard spiritual salvation as the beginning of life and, certainly, when that salvation is accompanied by the acceptance of Holy Orders, that new life has more than sentiment's viability.

In Buddhism as in Christianity we often speak of being reborn in the Faith. When, for example, a Roman Catholic is welcomed into the community and confirmed in his inclusion, he or she receives a new name - a Confirmation name. Just so, a Zen Buddhist is given a new Dharma name when he or she accepts the Precepts. The new name signifies that a new life has begun, that a clean and fresh identity has been established. In a very real sense, the person who previously existed has died along with his past. Frequently the sense of renewal is so strong that people will say, without exaggeration, that their life did not really begin until they became Christians or Buddhists. To a priest, his or her Dharma Age is often the only one that matters.

Buddhists have the additional problem of receiving a required lineage "surname" when they enter the faith. In Zen, the specific order of this list of one-syllable Buddhist-related names indicates which of the Five Petals of Chan Buddhism a person has embraced. A priest or master is obliged to give the name that succeeds his in the established sequence. He is additionally required to select another one-syllable name the meaning of which complements the lineage surname. This narrows the selection and often in a monastery or other religious organization headed by a single priest or a small group of priests, many people have the same name. One or two nicknames are usually given to identify an individual further and often, in the course of ministry, a priest may even adopt an additional name. Thus, Gu Yan was given the subordinate names Yan Che and and De Qing and later chose to be called Hsu Yun. In the Lin Ji (Rinzai) "Petal," a priest whose surname is Jy or Zhi must give the name Chuan, who gives the name Fa, who gives the name Yin, who gives the name Zheng, and so on until the list of several dozen names is exhausted and must begin again. This naming process has been in effect for more than a thousand years; and in the course of these years the same name has appeared an uncountable number of times.

Since a priest's Dharma Age usually begins when he is around twenty (the typical age of ordination), there commonly is a twenty year difference between his biological birth and the age which the priest regarded as the beginning of his only meaningful life. For anything other than modern times, such a determination is not easily made. Written accounts, if they ever existed, disintegrate or disappear. Wars and natural calamities destroy data or disrupt their collection.

Hsu Yun did not keep a diary. Instead; he memorialized noteworthy events, a selective method which left time-gaps that could be easily exploited.

The Procrustean stretching is readily seen in the Autobiography's opening pages in which the significant events of his early years, including priestly service, are distributed over forty two years. Vital information, such as parentage, place and circumstance of birth are vague and oddly nameless. We are left to wonder why Hsu Yun, who in fact, burned off a finger as a sacrificial offering to his mother's memory, would omit the mention of her name. But specificity defeats attempts to distort. It is as if the editor thought that the more nebulous the reference the more difficult it would be to delineate the stretching process In a mere 256 lines we are given a year by year account of the first 42 years of Hsu Yun's life. (It isn't until the age designated as forty-three that the record acquires the cachet of authenticity.)

Let us take a moment to consider the brevity of these first entries.

| Age | Lines |

|---|---|

| 1 (year, 1840) | 8 |

| (no entries for 2 through 10) | - |

| 11 | 5 |

| (no entry for 12) | - |

| 13 | 11 |

| 14 | - |

| (no entries for 15 or 16) | - |

| 17 | 19 |

| (no entry for 18) | - |

| 19 | 6 |

| 20 | 12 |

| (no entries for 21 and 22) | - |

| 23 | 9 |

| (no entry for 24) | - |

| 25 | 4 |

| (no entry for 26) | - |

| 27 | 28 |

| 28, 29 | 30 29 |

| 31 | 61 |

| 32 | 6 |

| 33 | 3 |

| 34 and 35 | 3 |

| 36 | 9 |

| 37 | 7 |

| 38 | 15 |

| 39 | 2 |

| 40 | 4 |

| 41 | 3 |

| 42 (year 1881) | 3 |

Total 256 lines for the first 42 years.

| Age | Lines |

|---|---|

| 43 (1882) | 21 |

| 44 | 103 |

| 45 | 266 |

| 46 | 37 |

| 47 and 48 | 41 |

| 49 | 61 |

| 50 (1889) | 127 |

Total 656 lines for the next 7 years.

That there should be such a dearth of information for the first 42 years with virtually no verifiable proper names given suggests not only the redactive stretching but also the deletion of any information that might be independently referenced.

The facts of sainthood would be better served by showing us a human being whose goodness and wisdom are all the more remarkable because he, being otherwise no better equipped to survive life's calamities than we are, steeled his indomitable will and prevailed. Instead we are given the portrait of a man who was most notable for accumulating birthdays and for occasioning minor miracles.

Even his birth is made miraculous: his mother died after expelling a uterine "flesh bag" in which he was sealed. He remained within the corpse, without fluid or oxygen, until, a day later when someone cut him out.

Without doubt Hsu Yun was the most humble of men; yet the words often put into his mouth convey an unflattering confidence in his supernatural powers.

When a man is credited with miraculous powers, hagiography has expanded into idolatry.

Repeatedly in the text, folk tales about Hsu Yun's supernatural abilities are woven into the first-person narrative. Heaven obeys his commands; and he acts with a sense of noblesse oblige. Often he is asked to come and preach to a group and when he arrives a miracle of sorts occurs: plants that had not flowered in a hundred years burst into bloom. Yunnan has been suffering through a five-month drought and a raging diphtheria epidemic. The governor "asked me to pray for rain. I set up an altar and within three days torrential rains fell." Snow would help end the diphtheria epidemic but it is too late - the spring is nearly over, but... "I prayed for snow. The next day a foot of snow fell." Were this the adulation of an onlooker it might be overlooked; but as such accounts are placed into his own mouth, they take on a disagreeable conceit.

As published, the two discourses which appear both separately and as part of the autobiography do not remotely suggest the man who was loved by millions. The account is not, to my knowledge, a transcription of taped recordings. The notes, compiled by attendees, are heavily edited or translated into English so ineptly that the style is didactic, flat, and tedious.

Can this be the Hsu Yun that to this day old shop keepers in Chinatown recall with tears of joy? The man we were introduced to in the English language was not even a ghost of the vibrant man the Chinese knew as Hsu Yun.

Shortly before I left for China for the 1994 ordination ceremony, Grandmaster Jy Din Shakya, Abbot of Hsu Yun Temple in Hawaii, asked me to write both his own memoirs, particularly as they concerned his beloved master Hsu Yun, and also to record the saint's teachings - "more like he spoke." I didn't know quite what that meant, but Jy Din certainly did. For many years, he had been Hsu Yun's official interpreter.

Although Mandarin is now taught throughout China, in former times, no less than twenty-nine different languages were spoken; and while they were all written the same - in ideograms - they all sounded quite different. Hsu Yun spoke Hunanese; and since Jy Din spoke Hunanese, Mandarin, and Cantonese, he was an invaluable assistant and traveled frequently with Hsu Yun to translate his lectures. He therefore knew by rote the various anecdotes and the style of delivery Hsu Yun used.

The problems Jy Din had with the publications, Master Hsu Yun's Discourses and Dharma Words and Empty Cloud, The Autobiography of the Chinese Zen Master, arose, I think, from two sources: people of Chinese descent who actually knew Hsu Yun had expressed their disappointment with his portrayal in the English translation; and also, more seriously, an unfortunate experience Jy Din had had with Charles Luk.

Just as the "Discourses" translation was being prepared for publication, Mr. Luk, wanting to enhance the text with Jy Din's treasured photographs of Hsu Yun and others, asked to borrow the photographs for inclusion in the book. Jy Din kept each framed photograph on his private altar; and every day, in all their names, he offered incense, fresh flowers, and prayers. Naturally, he was reluctant to part with the photos; but Mr. Luk, a professional translator, promised that he would take special care of them and would return them in a few weeks. When the book was published and Jy Din asked for their return, he learned that Mr. Luk had neglected to ask the publisher to retain the photographs; and in the absence of such a request, they were automatically destroyed. Jy Din was disconsolate.

Since his assistant Richard Cheung and I had worked well together on the Han Shan memoirs, Jy Din was hopeful that we could collaborate on a new version of Hsu Yun's teachings.

In 1988, when I first met Master Jy Din and Richard at Nan Hua Temple in China, I told them that in previous visits I had been given literature - written in Chinese - about Hsu Yun. Jy Din gave me even more unreadable literature; and then, in 1995, he arranged to come to Nevada with Richard to dictate his memoirs and some of Hsu Yun's favorite teaching stories.

Master Jy Din had been an American citizen for nearly forty years. He understood English but he spoke it with a heavy accent and little appreciation for syntax and grammar. Being the daughter of immigrants, I was used to "filling in the blanks." I had less trouble than most in understanding him.

Solving the "120 year" age problem involved mostly a reliance upon common sense; but the stylistic problem was formidable.

For me, this second problem - getting Hsu Yun into better focus, was, at first, agonizingly difficult. I knew several old Chinese merchants in Chinatown who had heard Hsu Yun speak, and I also knew a few people who learned some of his anecdotes from their parents. The story about hungry people who pool their vegetables to make soup came from a college girl who learned the story sitting on her grandmother's knee. A university reference librarian found a diplomat's recollection of Hsu Yun telling the story about the Prince who loved birds. An oriental gift shop merchant from Guangzhou (about whom I have previously written) told me the stories about the butcher who advanced credit to an ungrateful woman and about the tallest dwarf and shortest giant who were the same size; but he related the anecdotes as cold, bare-boned tales that did not jibe with his tear-brimmed eyes as he recalled Hsu Yun's telling of them. A few people I met at the Chinese-American Friendship Club looked through some of the literature I had brought from China and gave me additional material. But I could not put the stories together to make a saint who was any more loving and beloved than the one Cen Xue Lu and Charles Luk had made.

Every attempt was worse than the one before. In my frustration he was even less appealing than he had appeared in the other works. I had promised Jy Din an accurate portrayal of his beloved master; and all I could come up with was a pedantic old raconteur. I felt terrible.

And then, one evening, I began reading Martin Buber's Between Man and Man.

In a section that discussed Kant's "Questions" Buber opens the discussion with the following lines: "Rabbi Bunam Von Przysucha, one of the last great teachers of Hasidism, is said to have once address his pupils thus: ‘I wanted to write a book called Adam, which would be about the whole man. But then I decided not to write it.'"

I had to re-read the lines a few times before I finally "got" the ironic humor. And then I began to laugh. The good Rabbi could no more write a book that encompassed all the relevant facts "about the whole man" than he could swim the Atlantic. So, as if by his own choice, he "decided" not to do something that was impossible to do.

A few nights later I awakened in the middle of the night startled by the shocking revelation that Hsu Yun's style was ironical... that he, like Rabbi Bunam Von Przysucha, was charmingly self-effacing. I got out my notes, books, and tape recordings and reinterpreted his delivery style. I could not wait for dawn and then the 3 hour time difference to pass before I could telephone Jy Din. When he answered the phone I blurted out one question: "When Hsu Yun gave a lecture, did people laugh?"

"Oh yes," said Jy Din. "He very funny. Everybody laugh. Everybody feel good to hear him talk. Love him. He very very funny." I said, "Thank you, Master" and got to work.

After Empty Cloud was launched on the Internet we received many letters from strangers who told us how much Hsu Yun's lessons meant to them. Many said they had experienced a renewal of faith and were deeply grateful to this most extraordinary holy man.

The book listed Hsu (Xu) Yun's death at age 100 and restored at least some of the warmth for which he had become famous. All of the quaint miracles were omitted since there was no need whatsoever to gild the saint's beautiful lily.

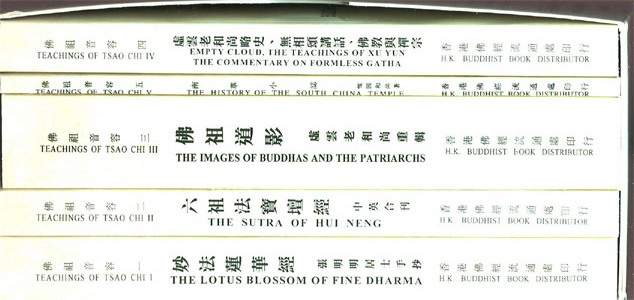

Our book was immediately published for free distribution at Hsu Yun Temple in Honolulu, Hawaii; and then, when Nan Hua Temple (Tsao Chi) published its 1500th anniversary commemorative boxed set of scriptures, our Empty Cloud: the Teachings of Xu Yun was included.