Home » Literature Archives » A Review of: Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter and Spring

A REVIEW OF: SPRING, SUMMER, FALL, WINTER AND SPRING

A film by Kim Ki-Duk

by Ming Zhen Zhakya

Kim Ki-Duk has given us a Soul's view of the world in this gorgeously filmed allegorical account of spiritual ascendance. There is no place specific to the place that he has used as his setting. There are no persons specific to those he has filmed. The Path to the spiritual summit is narrow and steep, and he has marked the route and showed us all the stages.

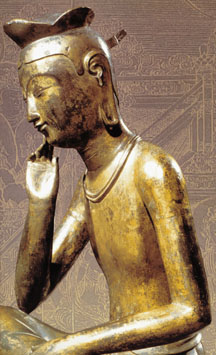

Astonishingly

beautiful bronze statue of Maitreya (Miroku) as a young man, dreaming

into existence worlds to come. Mirjok. 7th (?) Century Korea.

Astonishingly

beautiful bronze statue of Maitreya (Miroku) as a young man, dreaming

into existence worlds to come. Mirjok. 7th (?) Century Korea.

Following the coordinates of a divinely given dream-sequence, Kim's camera plots the trajectory of a Soul as it passes from its Nirvanic womb, through the birth cries of its loss of innocence and entrance into Maya's realm, Tattvas 36 to 6 - those principles of material existence that are referenced in the Heart Sutra. And finally he follows the soul through the Gateless Gate of Tattva #5, right on to the zero point of the Divine Couple's offspring, the exquisite Miroku... Maitreya, the Future Buddha, caught by a sculptor as He dreams into existence the material world.

Kim has taken us to the nexus of the Triple World's realm of desire, its realm of materiality, and its realm of the spirit. Desire functions as the interface between the real world of the spirit and the illusions of the material world.

When we acquire knowledge of ourselves as independent beings, the gates to the material world open. These sensory gates enable our illusionary human egos to encounter and then to covet the alluring but equally empty forms of the material world. We suppose that we are seeing and hearing the real world. We are not. The real world is inside us, in the spiritual realm of the Buddha's Refuge, and we must learn the hard way, through bitter and painful experience, to shut our sensory gates against these deceptive external attractions.

It is desire that causes us to leave the Buddha's Realm just as it is desire that drives us to return to it.

That the film is not to be taken literally is immediately made clear by the improbabilities of the setting and by the magic that is so easily accomplished:

An Old Monk, with virtually no means of support, a young boy, and a few animal pets, live on a temple raft that is mysteriously anchored in the middle of a high, circular mountain lake. But it is fixed like the axis of a wheel, and time and the shore can revolve around it.

The temple's interior is one single space; but while there are no walls or partitions, there are doors through which the occupants pass.

Outside the temple doors, in the raft's deck, a coy pond is embedded; inside, on the altar, more fish swim in a bowl over which the Buddha Akshobhya - the Great Mirror Wisdom, (Prajna) presides. The Buddha's right hand is conformed in the bhumisparsa mudra. "I call upon the earth to bear witness!" This Buddha is associated with the East and, therefore, with the reappearance of the spring sun.

There are other indications of the setting's mystical nature. The boy, having taken the only rowboat, has gone alone to the mountain's shore, leaving the old monk behind on the temple raft; yet he is overseen in his mischief by the old monk who has transported himself across the water.

Wearing a white dress, a girl, who has been both ill and chaste in her responses to a young monk, sits by the edge of the temple raft. The young monk suddenly pulls her into the water, causing her to lose her shoes in the lake. He rows to the shore and she goes barefooted to a matter-of-fact assignation on the rocks. Yet she returns wearing shoes and dress that show no sign of dampness or dishevelment. (A shoe figures prominently in the film's "feminine/water" symbolism.)

As an adult, the young monk is portrayed by three different actors, reinforcing Kim's obvious intention to convey the information that this man is everyman who yearns, who errs, and who succeeds in his spiritual travail.

The old monk can summon the boat at will... or he can retard its progress despite the forward motion of a strong rower.

The gates to the lake's dock contain the painted effigies of the powerful door gods who have control over all disembodied spirits. Using their own power, the gods can open and close the gates.

Kim has taken us into a mystical world where the Heart Sutra's wisdom will apprise us of the necessary sequence of events.

In Buddhism, the omniscience of God is understood quite simply as the spiritual presence within each of us of the Buddha Self, who is privy both to our thoughts and to our deeds. Yet we know also that the Buddha, though he be in the body of a saint, sees no saint, and though he be in the body of a murderer, sees no murderer. This love is unconditional.

In his film, Kim assigns the identity of the omniscient Buddha Self to the temple raft's old master. The Soul in its natural state of egoless innocence is the boy who, as the film begins, is - because of his purity - impervious to even the venom of snakes. Insouciantly he tosses aside a cobra. Nothing can harm the truly pure.

The boy and his master return to the temple; and it is then, while reviewing the choices he has made in the selection of the herbs he has collected, that the boy is introduced to the concepts of good and evil, of benevolence and malevolence, i.e., of curing and killing. The master shows him how to recognize those characteristics which separate the medicinal from the poisonous. He learns the difference between help and harm.

It is this knowledge of good and evil that ushers the boy into the dream of material reality where this knowledge will be tested.

The soul is born into paradisiacal innocence; but then, when it discovers its own ego identity, it discovers desire; and coveting what it sees and hears and smells through the small gates of the illusory mind, it casts itself out of paradise. Now in the material world, it becomes vulnerable to the unruly instincts of survival. Only if we are very lucky, can Paradise be regained.

The temple's rowboat bears the painted image of Guan Yin as she extends a hand that holds the lotus-born child Maitreya (Miroku), the Future Buddha. As the material-world sequence begins, the boy-soul takes this rowboat - his yana (the vehicle by which we are transported to our spiritual destiny) to the mountain shore. His Buddha Self (the old monk) mysteriously appears, observing his actions.

Kim pays homage to Buddhism's Middle Way. While the omniscient old master looks on, the boy joyfully torments three creatures.: he ties a stone to each of them: a small fish; a frog, and a harmless snake.

The choice of creature suggests the three Ways we can respond to life: we can choose the lower, water-dependent realm of the emotional body (Eros); or the higher, sun-depedendent earth realm of the spiritual intellect (Logos), or, we can find the harmony and balance of these two realms in the Buddha's Middle Way.

The fish, then, is a creature of the water; the harmless snake; a creature of the rational earth; and the amphibious frog, a creature of the Middle Way. Of the three, only the creature of the Middle Way survives the torment.

Forced to empathize with those it has tormented, the soul knows that it has now committed its first sin. It wails piteously; for its error has officially delivered it into the material world. Spring, the season of new life, is over.

Summer finds the boy a young man who is eager to see, smell, hear, and touch the alluring objects of the world. He watches snakes copulate and then looks up to see a girl who has come to the old monk to be cured of an illness. He does not love her; indeed, he does not even know her. But immediately he craves her sexually.

Love is a balance of desire and charity's thoughtful consideration. While the Soul loves it acts in a way that is natural to it. No place is too sacred for love. But lust and its insane obsessions are a foul descent into emotion's watery matrix. And in that realm we destroy and are destroyed.

We will learn the first two of the Buddha's Four Noble Truths. Life in the material world is bitter and painful; and the cause of this bitterness and pain is desire. The last two of the Buddha's Truths will be realized in penance and atonement, and a disciplined adherence to the steps of the Eightfold Path.

Though the Soul is warned of the terrible consequences of desire... of lust that must possess and in possessing, destroy, the soul goes its way, recklessly determined to possess what only God may possess: the Soul and the Life of another human being.

Helpless to overcome his desire, the young monk pursues the girl when she is apparently cured and leaves the sacred lake. Summer has ended.

Buddhism teaches us that it is foolish to try to calibrate that which is immeasurable; that these material illusions are merely the causes and effects of infinite causes and effects, that Time and Space and the Light that illuminates it exist only in the Buddha's Realm. All else is darkness; and we can only stumble through immensity, foolishly confident that we can encompass it and give substance to our illusions.

The young monk's ego, poisoned by lust and anger, is in the thrall of the material world's skandhas, the illusions that he feels, perceives, wills, and cogitates, grandiosely assuming he can control the Realm of the Spirit.

In such a state, the soul inevitably kills the thing it seeks to possess; and like a thief in the night, creeps back to the Refuge. But its heart is filled with pity for itself; for its own defeats. It curses what it could not conquer, blames it; and seeking to be free of the torments it has brought upon itself, tries to shut the doors to the realm of Maya - never supposing for an instant that it is on the wrong side of the Gateless Gate. It feels no compassion for its victims. And the Buddha Self scourges it for this sacrilege.

The ceremonial knife, the Ju, still bears the blood of its victim. But this knife is far from being ready to belong to the Ju Lai, the Future Buddha.

The Buddha gives the soul the words to the Heart's Wisdom and tells it to use the knife to inscribe the words, to carve them into itself and by this writing purge itself of the poisons and anger and lust.

The monk completes the carving; concluding the first phase of the Opus. Two guards escort him back to the material world to pay for his crimes; and there he will test his understanding of the Sutra.

The old monk piles some firewood in his rowboat yana, lights it, and in an act of self-immolation, retires to Parinirvana, leaving behind his spiritual presence in the form of a benign and amphibious snake which swims safely to the Temple raft. Winter has now come to the lake.

We well know that not until the soul has completed its penance does it understand the Great Wisdom of the Sutra. The monk, released from the material world's prison, returns to the Buddha's Refuge. He walks through the Gates, needing no yana but his feet as he walks across the now frozen waters of emotional desire.

He is now mature, chastised, and prepared to complete the Eightfold Path's steps.

First he retrieves from the ashes at the bottom of the rowboat, the Buddha's Sacred Pearl relics (teeth and bone fragments which have transformed into pearl).. He wraps the Pearls in a red cloth (which represents the flame "jyoti" or "tilak" spot between the eyebrows which indicates the Buddha's 3rd Eye of Wisdom) and inserts the small red bundle into the point between the eyebrows of a statue of the Buddha he has carved out of ice.

He undergoes the discipline of Qi Gong. And in meditation, at the center of the Wheel of Life, he fulfills all Eight of the steps. He is ready to be one with the Bride.

Guan Yin, as Isis, veiled to all but the soul who encounters her, comes to him, staying only until the consummation's fire has died into connubial ash. She leaves the divine child Miroku with her consort and returns to the depths.

Now the soul can climb to Enlightenment's summit and as Miroku, sit upon its pedestal and dream the material world into existence.... or not.