Home » Literature Archives » Knowing When It's No We Can't

Knowing When It's No We Can't

Photo Credit: www.oglethorpe.edu

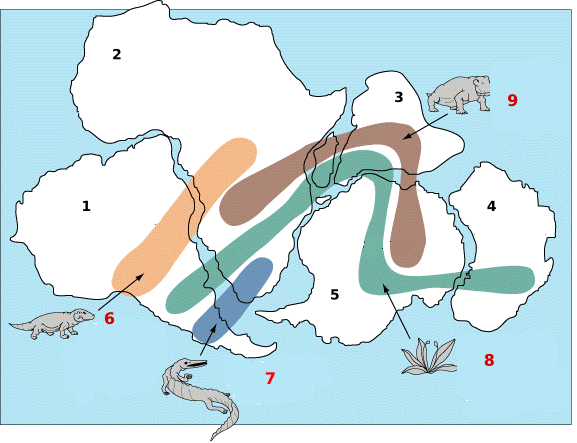

Photo Credit: www.oglethorpe.eduAntonio Snider-Pellegrini and Alfred Wegener showed that the location of fossil plants and animals on continents that are now separated illustrates early connection. Wegener's 1912 theory of Continental Drift was met with mocking disbelief by his scientific peers until 1960 when irrefutable proofs were adduced.

Along with many glimpses into the emotions of a bored, shopaholic housewife, Gustave Flaubert allows us to stare into the grotesque results of irrational beliefs.

It is an oddity of human behavior that a person who is not qualified to perform a certain task will, if given an effective stimulus, discard all common sense and believe that he has suddenly become an adept. Although he possesses only the idea of skill, he is able to induce others into believing that he is, in fact, skilled. It is as if he is a vector of one of those virulent diseases that leaves the carrier asymptomatic but spreads the contagion to those around him.

In life, as in Madame Bovary, the thought of gaining fame and fortune sets disaster in motion.

In the novel, a small town pharmacist, who is frequently called upon to give medical advice, naturally considers himself a physician of sorts. As such, he reads with interest all the latest "big city" medical news. An article about correcting a club foot's congenital error immediately inspires him since, fortuitously, the town happens to contain an impoverished club-footed individual, a young and lonely stable boy who also, as luck would have it, is not very bright. The town also contains a doctor who just might be liberal enough to attempt something new.

He sees the three types of club foot deformity with the simplicity as might describe the misalignment of one of a ship's axes: a yaw, pitch, or roll. A constricted tendon has forced the foot into its disordered twist, and the obvious solution is to determine which tendon is guilty of shirking its duty and then to cut it. The leg is then placed in a device which will prevent the tendon from assuming its slothful ways, forcing it to re-grow itself to the needed length. It is an ingenious solution!

The pharmacist is seized with patriotic fervor. As welcoming signs to a small town inform the visitor that he is entering the Collapsible Ladder Capital of his country or its Home of Yellowjacket Honey, he sees his home address as being among those proud individuals who share residence in the Club Foot Correction Center of his nation. But the pharmacist, now a visionary-vector, seeks more than just hometown prestige: there is the personal pride of sponsoring achievement, of being a "kingmaker," and of having his image stamped forever on the newly minted hero.

The pharmacist's zeal is first transmitted to Emma Bovary whose appraisal of her country-doctor husband has recently reached a new low. Dr. Bovary has long been distressed by his wife's coldness towards him, and her sudden attentions therefore delight him. Even though he lacks the knowledge and experience necessary to conduct such a procedure, he readily agrees to perform it. She will be his surgical muse! She is so angelic when she describes those joys that the hobbling stable boy will experience when he is able, at last, to whirl across a dance floor or to march in a parade - events that will be noted in newspapers to an adoring public. Naturally, she keeps to herself the thought that her husband's fame will command more income - a benefit greater to Emma Bovary than all the waltzing and goose-stepping in Christendom.

Dr. Bovary, filled with heroic confidence, orders the necessary medical text to study.

The stable boy is not so easily convinced. It is an age in which surgeries are performed without the niceties of anesthesia, and he has perhaps known enough of pain to hide when he sees it coming in his direction. But the town's leading citizens are already infected with boosterism. His expected pain varies inversely with their increasing desire to reside in an important place. He is assured that his pain will be no more than that incurred when having a corn removed from a toe. And naturally, submitting to such a minor inconvenience will enable him to fulfill his civic duty. Since it is this club foot that exempts him from military service, its correction will permit him to wear the coveted uniform. And as to the procedure's cost, Dr. Bovary generously offers his services freely; and further, at his wife's insistence, he will also bear the cost of manufacturing the leg straightening device.

The book arrives, and Dr. Bovary finds himself totally bewildered by the technical language and the anatomical subtleties of the deformity.

When the time comes to make the surgical incision, Bovary shows his lack of experience. He doesn't make a decision, he makes a guess.

Most people, but not, apparently, Dr. Bovary, know the story of Thetis who gave her son Achilles immortality by dipping him into the River Styx. Achilles remained vulnerable only in the one place the saving water could not touch him - the place where his mother held him during the dipping - the point behind his ankle. With all the town's important persons watching, Bovary severs the stable boy's achilles tendon. The pain is minimal. The town cheers. The leg is placed in the straightening box; and everyone is happy until a week or so later when infection turns to gangrene, hope becomes screaming agony, a real surgeon is summoned, the rotting leg amputated without anesthesia, Bovary is considered a fool by everyone, and his wife's opinion of him plummets from disgust to the depths of loathing.

Well is it written that success has many fathers while failure is an orphan.

After a brief hangover, the town's intoxication dissipates, and all are left soberly conscious of Bovary's incompetence just as they are oblivious to their own participation in the debacle.

Anytime a new opportunity is presented to us - by someone else or even by ourselves as an idea that suddenly occurs to us - there is a momentary vacuum of opinion. We don't know if there is merit in the new person or idea or whether we should close our mind to any possibilities. It is then that we are susceptible to a thousand different influences, any one of which can rush into that vacuum and irrationally fill it. The problem is that emotion is usually the source of that influence; and emotion is a terrible arbiter of merit.

Leaving love affairs and such aside, the two instincts/archetypes that influence us are the hero and the shadow, the latter being opposites, like two sides of a coin: the friend and the enemy. It is sometimes difficult to understand how the friend and the enemy arise from the same emotional source. The easiest way to understand it is to view the concept in the way that men in prison see it. Many of them have had a best friend or even a brother with whom they were arrested for having committed a crime. The coin is a perfect analogy. The prosecutor immediately tries "to flip" one of the defendants; to get him "to turn" state's evidence. There is nothing more shocking than to discover that a friend - who might even have been the one who suggested doing the crime - has now become our enemy. He's taken a deal and will be testifying for the prosecution.

We know how quickly a friend can become an enemy if we lend that friend money and he doesn't repay it but does spend it on luxuries we cannot now afford. Instead of repaying us as he solemnly promised he would, he may even tell anyone who will listen how much he did for us and neither asked for nor received a cent even though what he did was far more valuable than the paltry sum we gave him.

Sometimes, as a kind of blessing, we are surprised and deeply affected to learn that someone we regarded as an enemy has done something beneficial for us or has spoken kindly about us.

The significant fact of arousing an instinct for or against someone is that the moment we make such an emotional connection, we immediately become blind to his faults if we like him or his good qualities if we dislike him. This can be dangerous when it comes to friends or enemies. It can be deadly when it comes to heroes.

If we suddenly get a bright idea, our hero archetype may rush into our own psyche, inflating it. We begin to see an exponential increase of benefits that will accrue from the idea: product expansion, power, money, a Ferrari, a big house in the suburbs. A secret euphoria and sense of omniscience envelopes us. And if it happens that our idea begins to deliver on its promise, we are covert megalomaniacs.

We will have friends, usually more new than old. And because we are inflated with the hero, we must have enemies since a hero requires a dragon to slay.

If the hero and his idea are presented to us by someone else, much will depend on circumstance and on our particular area of vulnerability. In a Ponzi scheme, for example, the one who presents the hero may be someone we trust who has just made a large profit from his perspicacity. Our friend may innocently confide to us the wisdom of investing with the crook. Now we have our moment of indecision. We know that our friend doesn't know any more about "the market" than we know. And we have heard of Ponzi schemes. Yet, we tend, somehow, to trust his judgment. Why?

Usually each of us can count on having at least one weakness, some of us have an abundance of them. The Seven Deadly Sins are not a whimsical invention. They are usually the reasons we need money and are willing to take risks. We may be insatiable when it comes to food, drink, sports, gambling - all evidence of gluttony and a good use for profits. Lust needs no elucidation, only the cash to pay for it. Pride always comes before a downfall as Proverbs tells us. It is the expensive prelude to a dirge of our own composition. Should our friend mention a few celebrities who are in his investing "circle," our vanity will kick-in and the temptation to penetrate that circle's perimeter will be too great to resist. Greed is the most poisonous sin since it will so envenom us that we will toss grandmom under the bus if we hope to benefit financially from her demise. Sloth is what we do best; and we chide ourselves for it - usually when it prevents us from pursuing the other six sins. For us, jealousy is what frequently causes anger and tends to be the only thing that faithfully motivates us.

Regardless of our weakness, we conclude that our friend's broker is superior to ours. The 'indecisive moment' passes. We write the hero a check. Our BFF pats us on the back and welcomes us into the fold.

While it is true that heroes deliver treasure, the treasure does not have to be intrinsically valuable. He may restore our honor and dignity - or promise to; he may free us from oppression - or promise to; he may deliver us to a promised land. Jonestown comes to mind. Often, the hero has discovered a way to right a wrong which we may or may not have previously noticed. He must be personable, i.e., attractive in his appearance or charming in his disposition. He must generate excitement since it is in rising emotion that archetypal energy is projected. Again, once we have made an emotional attachment to him, we are blind to his faults. When the difference between what has been promised and what has been delivered becomes great enough, we curse him for his failures and absolve ourselves for having been so easily taken in.

A good way to avoid following the lead of a fake hero or trusting in those who are not trustworthy is to try to analyze the approach that is being made and then to play our own Devil's Advocate and deliberately seek reasons why we should say No to the offer. Once we purge emotion from consideration, the Yes or the No will stand on its own merit.

There are reasons we get suckered into foolhardy schemes and reasons why we obstinately turn away from rational explanations, and seldom do those reasons have anything to do with reasoning. Evaluating something new requires the bold disciplines of rational thought; and it is so much easier to retreat into conservative safety's old beliefs. Why, for example, couldn't scientists see the obvious geographical configurations that Wegener saw as Continental Drift? Why else but that they responded emotionally. Their sense of fellowship was strengthened by casting their collective shadow on him and dismissing him contemptuously. The Alvarez father and son team's theory that an Asteroid Impact 65 million years ago marked the end of the age of dinosaurs was similarly greeted with contempt by peer groups when they first presented it.

Readiness to believe an absurdity indicates the same failure to think constructively. In 1973 Jim Jones decided to establish Jonestown in (British) Guyana and also in 1973 the Oscar nominated film Papillon appeared. No one wondered why Jim Jones' "Temple Paradise" was so close to Devil's Island - just off the coast of French Guiana. What made a group of Christians forget that Jesus said the Temple of God was within. No one had to go anywhere to enter the Temple. What led these city dwellers to believe that God wanted them sell everything they owned, give the proceeds to their hero, and joyfully take their children to South America to farm a jungle?