Home » Literature Archives » TATOO MESSAGES

TATOO MESSAGES

By Ming Zhen Shakya

--The narrator of The Illustrated Man, by Ray Bradbury.

Some things in life that are not in the least technologically complicated still manage to confound us - not superficially, but at their originating depths. We may examine them at length and regard what we see as admirable or disgusting, yet their essential nature remains surrounded by a mysterious aura that we can never quite penetrate. As observers of a bullfight, for example, we can easily describe the matador and his golden "suit of lights" while being completely unable to comprehend the man, the peculiar uniform, or the underlying purpose of the spectacle. Just so, a man and his tattoos - the scenes and messages he has permanently fixed in his skin - present recognizable forms that we can judge to be beautiful or ugly while yet being puzzled by their reason for being which remains strangely inscrutable. In either case, the display usually leaves us fascinated, but not alarmed.

(When, however, Ray Bradbury's narrator described the scenes engraved on the illustrated man, he had not yet encountered that one blurry spot in the exhibit that never failed to terrorize the unsuspecting viewer.)

In Polynesia - where the name "tattoo"originated - and in a few other parts of the world, the practice of tattooing has had a long, honored, and uninterrupted history. Elsewhere, for probably as far back as the week that Homo sapiens first became a distinct species, tattooing has experienced cyclical popularity. Among the reasons cited for causing a nadir in the cycle are religious objections that revive Scriptural prohibitions, and, since tattooing requires breaking the skin's natural barrier to infection, governmental restrictions on the practice in response to disease blamed on unsanitary procedures. It is far more likely, however, that a routine "cycle of fashion" causes the shifts in interest.

Fashion's cycle is familiar to consumers: "introduction of an innovative style; favorable reception; excitement of emulation; de rigueur status; novelty's fatigue; exaggeration of the innovative feature to spur diminishing excitement; excess; decadence; and enantiodromia" - as when, for example, the gussets, inserted into bell bottom jeans to widen them, expand into a ludicrous flair and the entire fashion is abandoned in favor of skinny-leg jeans.

We can expect that when the current tattoo craze reaches its zenith of fashion and tattoos become commonplace, interest in obtaining them will decline - but not disappear. There will always be a core-group of people who like the idea of permanent commitments and are willing to pledge themselves to a person or idea by the medium of ink.

In any event, for as long as they are en vogue, such body art and insignia become status symbols that are far more potent than material acquisitions or personal accomplishments. They capture our attention and influence us. Money and fame come and go. Tattoos have the shelf life of diamonds.

The exception, of course, is the individual's desire to change or remove a tattoo. It should surprise no one that far more women than men have tattoos removed. Women, as we all have begun to suspect, change their minds about philosophical truths, men, and a variety of other less interesting topics. Additionally, they tend to dislike being reminded of former attachments. Since, in their fashion choices, women generally show more skin than men, it often happens that a tattoo will interfere with a garment's design. A dress's cut may partially hide the tattoo's message or the dress's fabric may visually clash with the colored art. And no one can escape the truth that sagging breasts and postpartum stretch marks can distort an image, or, as a woman ages, messages that were once inscribed on plump skin will shrink into indecipherable wrinkles. The sight of such crumpled art does not act as an inducement to younger women.

Occasionally, the need for change is more egregious. A woman who records on her neck that she will be eternally devoted to John would be wise to remove the pledge before she walks down the aisle to marry Larry. Of course, a clever tattoo artist may be able to convert the name "John" to "Larry" - but divorce rates, being what they are, removal would be better. Former Nazis really ought to convert their swastikas into floral bouquets unless they intend to live in the Orient - where swastikas are a disconcertingly ubiquitous reference to Buddhism. But for a woman, there are probably more reasons for removing a tattoo than there were reasons for obtaining it. In this, it is rather like divorce and marriage.

Ray Bradbury's illustrated man wished, to the point of desperation, to eradicate his tattoos. His body art had been applied by a woman who "went back to the future," a woman he regarded as a witch whom he would happily kill were he ever to encounter her again. She had created eighteen separate scenes on his body, and though they were painted in exquisitely beautiful detail, they could be admired only during the day. At night, the characters in all of the scenes would come alive, causing the illustrated man to feel considerable distress. As the characters struggled, suffered, and died, he could feel their agony and grief, and so could the people who saw them. This experience was so intolerable to the viewers that they quickly drove him from their sight. For this reason, he could never hold a job or live a normal life.

But worst of all was that blurry spot on his right shoulder. When a person stared into that nebulous area, a scene would create itself in which the viewer would see his own horrible death acted out before him. Bradbury's narrator decided to risk staring into the spot, and saw himself being strangled by the illustrated man.

With the possible exception of Antarctica, every continent on the planet has been populated by people who have proudly displayed "inked" tribal and familial affiliations and the logos of clubs, military groups, or other associations. Universally, tattoos that convey magical pronouncements remain popular because of our ingrained notion that words, themselves, have such power as to confer the effects of their own definitions. Likewise, real or mythical animals and birds, notable for a fearsome quality of power, cunning, protection, or stealth, are also assumed to inspire the wearer to increase his efforts to exhibit the special qualities of the creature that has been engraved upon him. Dragons, snakes, eagles, phoenixes, and tigers find a welcome habitat on warrior arms.

Most often, a significant event - such as war, a rite of passage, or the discovery of one's true love, initiates the desire to memorialize the event with ink, brand, or blade. Occasionally, a celebrated person will flaunt a tat and inspire hosts of admirers to imitate the action. A tattoo may also receive special attention by being the focus of a dramatic work.

Photo credit: shooting-star-tattoo-gallery.com

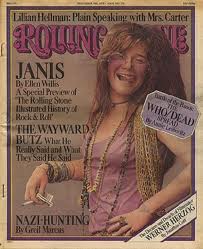

For women, a tattoo on a "private" body part became acceptable once Queen Victoria allegedly obtained one. But for those tattoos that were publicly displayed, it would take a hundred years and the boldness of Janis Joplin to make "ink" a symbol of women's liberation. She proudly displayed the Florentine wristband created for her by tattoo master Lyle Tuttle.

Photo credit: Wikipedia.org

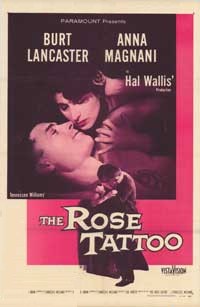

In the 1950s, Tennessee Williams wrote The Rose Tattoo as a starring vehicle for the great Italian actress Anna Magnani. With the help of Burt Lancaster's chest, rose tattoos rose to the top of floral motifs.

In 1981's film, Tattoo, actor Bruce Dern, playing a tattoo artist, falls in love with Octopussy Maud Adams. He abducts her; and in the isolation of his old seaside home, keeps her drugged while he decorates her body with floral bouquets. When she is first conscious of what he has done, she is horrified; but then the beauty of the display captivates her and she happily yields to him.

Photo Credit: Bellaonline.com

Photo credit: Bellaonline.com

Adams and Dern in 1981's Tattoo

photo credit: starcasm.net

Most recently, the incomparable Noomi Rapace, "The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo," has revived an international yen for full-back oriental dragons, they being the principal Yang symbol of strength, intelligence, independence, and good luck.

Religion, too, has provided the inspiration to emblazon one's body with the images of spiritual conviction. Externally. such a tattoo serves to remind the person who wears it of the personal vows he has made to conform to his religion's ethical standards. The tattoo also serves to make the viewer aware of the person's religious affiliation and, as such, functions as a kind of advertisement. Internally, however, such a tattoo is an offering made in gratitude for the blessings experienced by the person. The cost of the tattoo and the pain involved are incidental. The person has dedicated part of his body to glorify his god or saint.

Guan Yin (Kannon) has won the devotion of countless Mahayana Buddhists. Long considered the Bodhisattva of Compassion both as a female goddess and as an androgynous bodhisattva, Guan Yin/Avalokitesvara has been unabashedly admired by John Blofeld and many other authors, as well as numerous sculptors and artists.

Yin Shan Shakya, Zen Buddhist Order of Hsu Yun's personnel director, recently dedicated the surface of an entire arm to the glory of Guan Yin. Tattoo artist Kevin Marr of Godspeed Tattoo, placed the Bodhisattva, the fetal Future Buddha Maitreya, and Yin Shan's priest' seal amid a floral display.

Yin Shan explains, "Back in grad school, a colleague of mine named Michael Sheehy - now book editor for Buddhadharma Magazine - gave me a brass Guan Yin statue. It was his generous recognition of my long standing affection for the Bodhisattva. The statue soon became the focal point of my devotion; and all the Guan Yin symbolism that I had studied and appreciated in school quickly coalesced into a singular fixture of love and dedication in my Buddhist practice."

"Wearing one's heart upon one's sleeve" in print or image is an expression that indicates total devotion and loyalty to the one who is so named or depicted. Yin Shan's commitment to Guan Yin is further proven by his steadfast support of our Zen ministry.

Here, courtesy of Godspeed, is his tattoo:

Note: The Illustrated Man can be purchased at any bookstore or freely read at Fileden.com