Home » Literature Archives » ERASERHEAD: a Commentary by Ming Zhen Shakya

ERASERHEAD: a Commentary by Ming Zhen Shakya

David Lynch added yet another layer of mystery to Eraserhead when he revealed that it was a line he read in the Bible that finally cohered elements of his film that had begun to diffuse dangerously. Insisting that the film was his most spiritual work, he, after several years of working on it, had lost control of his original vision; and then, while reading the Bible, he came upon a line that "pulled it all together." Although he has declined to disclose the "chapter and verse" of this revelatory line, it is this spiritual aspect of Eraserhead that is of interest to us, the techniques of film making being quite beyond our ken.

Great art has four absolutely essential qualities: It must arouse our emotion; our imagination; our reason; and it must survive. Had Plato seen Eraserhead he would, assuming it were great art, have given it as much consideration as della Francesca, Gandhi, or the folks sitting around me when I saw it for the first time thirty years ago. No one can have any problem with the film's ability to arouse emotion and imagination. And since we're still talking about it and are likely to continue doing so, we are left with the elusive quality of reason. What did this film mean? Since its creator has categorized it as spiritual, we must seek its definition in our religious lexicons, though we will likely have to plumb new depths of meaning to access it.

Whatever its lifetime, a work is still haunted by the zeitgeist of its time in utero. Eraserhead's time was dominated by our universal fascination with outer space. The Apollo program, Kubrick's 2001, and such TV shows such as Star Trek, all kept our attention on the cosmos. Surely the most startling photograph of the era (if not of all time) was Astronaut William Anders' December 1968 "Earthrise."

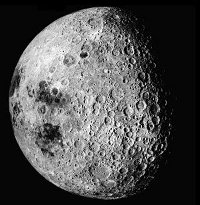

It is a celestial image of this type that Lynch chooses to open his black and white film. A horizontal man, Henry Spencer, the film's central character, rises up slowly until the cosmic body is superimposed upon his own braincase.

The dark side of the moon.

The plot, such as it is, catalogs the symptoms of Henry Spencer's human condition. There are bizarre contradictions, inexplicable events, actions without apparent motivation. It is, in short, a slice of Everyman's life, a slice of the same dumb-animal samsaric pie with which we are all lamentably familiar. Henry's time is allocated by a demonically disposed fate.

Divided loosely into scenes, the film shows us that after his head has melded with the dark celestial body, his mouth opens to allow a worm-like creature to escape and wait outside his face, poised for launch by the demonic cosmic director, who pulls a lever and sends the worm on a journey through a "dawn of creation" aperture in space that terminates in a scummy pond.

After a long moment's darkness, we see Henry shuffle determinedly across barren ground. He wears an ill-fitting business suit and the chevron of a nerd: a white plastic pocket protector which holds a half dozen or so pens and pencils. Henry passes through an ugly but monumental doorway which is merely a portal to another even more bleak moonscape. His right foot steps ankle-deep into a puddle, but undeterred, he continues his mission to return to his home.

Henry lives in one room in a hotel. As he unlocks his door, a pretty woman who occupies a room across the hall, delivers a message she has taken on the floor's pay phone: the parents of his former girlfriend, Mary, want him to come to dinner that night. He thanks her, enters his room, and plays a recording of a calliope on his phonograph as he sits on his bed and removes his left sock to lay it across the radiator to dry. (Only God and David Lynch know what this means.)

The radiator is a kind of cathedral to him. He stares into it and the night sky, filled with stars, appears to him. When his meditations are realized a blonde girl dances on a carousel to the calliope's music. Large sperm-like creatures fall from above. She dances and deliberately steps on them until they spurt like so much ejaculatory matter. His fascination and the sexual symbolism are not difficult to understand. He is not always successful in his fantasy assignations; but that she is his promise of paradise there is no doubt.

Preparing to go to dinner, he goes to a chest of drawers and removes a photograph of Mary that he had torn in half. Evidently, he had not envisioned a future with her; but now he holds the two parts together to show us a rather pretty girl's face.

Along a desolate railroad track, Henry walks to Mary's home. Once inside he meets her family for the first time; and finds himself confined with people who do not quite understand that they are human beings. While Mary has a fit which her mother ends by violently stroking her hair, Henry explains his occupation: he is a printer who is on vacation at the moment. Her father, Bill, becomes agitated about his own contribution to the over-developed decay of the world; and to his wife's chagrin begs Henry to examine his knees.

Asked to carve the roasted chickens that for a reason which defies explanation are "man-made" tiny, scrawny birds, (perhaps this is a commentary on the plastic nature of fast food), Henry stares incredulously as the headless and footless bird on his plate begins to dance suggestively and to bleed. Mary's mother lapses into a speaking-in-tongues kind of trance and finally runs from the room with Mary following her.

Mary has just given birth to a premature "baby" (she is not sure what it is) but her mother insists that it is a baby - Henry's baby - and that he must therefore marry Mary. He instinctively demurs, but her mother coaxes him into revolted submission by attempting to make love to him.

Married and at home in his one room apartment with the baby - and here David Lynch should say the Rosary ten thousand times in gratitude for PETA's not being around to object to his "baby" which, frankly, appears to be a still living, skinned baby lamb. Its head and neck are visible; but the rest of its body is wrapped in gauze. When people call this film a horror film, it is to this "baby" they are referring. (Clearly, among women viewers, maternal instincts tend to arouse sympathy for the creature; while male viewers tend to see it as the monstrous result of a simple sexual liaison - a result which should have been quietly aborted.)

The "baby" makes pathetic sucking noises of pain and hunger; but Mary does not breast feed the infant; and it does not want - or yet cannot eat - the spoon-fed food she offers.. The baby cries incessantly.

In dialog that could have been taken from any household in the civilized world, Mary screams in frustration at the baby, ordering it to stop crying. The baby, in this instance no different from any other baby, doesn't obey; and Mary announces that she can't go on like this. She needs one good night of sleep or she will go mad. She leaves, instructing Henry to take care of the baby while she is gone.

Henry discovers that the baby is very sick. It is covered in the boils and blisters of strange sores, and also it has difficulty breathing. He connects a vaporizer, and then, when the baby seems calmer, he attempts to leave the room. But the baby cries even harder whenever Henry opens the door to leave. So he sits and waits for the vaporizer to fully ease the baby's distress.

Ultimately, Henry has sex with his neighbor, but his biggest thrill is the satisfaction he derives from the blonde dream girl who lives inside himself (i.e., the radiator), although the baby's crying increasingly frustrates his attempts to contact her.

In one successful encounter, the radiator's interior stage stops turning and Henry bravely climbs up onto it. Her song has altered. she now adds a verse which gives him an ambiguous but encouraging forecast for the pleasurable communion he believes awaits him in her carousel paradise. Her song, "In heaven, everything is fine. You've got your good things and I've got mine" suddenly becomes, "In heaven, everything is fine. You've got your good things and you've got mine."

He timidly reaches out to her, and her touch brings dazzling light. The light is clearly meant to be a divine vision. From the Bhagavad Gita we read: "Suppose a thousand suns should rise together into the sky: such is the glory of the Shape of Infinite God." He momentarily recoils from the light and then touches her again, and after another burst of blinding light, she disappears and a squeaking wagon containing what appears to be dirt and a barren tree, reminiscent of Beckett's tree in Godot, rolls slowly onto the carousel. Suddenly, Henry's head is severed and punched out of his collar by a large penis. His head lands on the carousel floor and is soon inundated by an oozing substance that comes from the tree's base. The penis is replaced by the screaming baby's head as Henry's head sinks into the ooze and is then catapulted out of the hotel onto a dirt landscape.

A child finds the head and carries it to the pencil maker. And now the message becomes more clear: The God of the Pencils employs Henry's brain tissue as an eraser which he fits atop an ordinary yellow pencil. He sharpens the pencil and draws a line... this is the samsaric lifeline Henry's life has been following. And, using the eraser, the "God" removes the line from the paper. He blows the worthless eraser dust into the air and Henry awakens. That our past transgressions are so easily eradicated when we have the courage to "touch" divinity is a fact known to any person who has experienced the ultimate purposes of his faith.

Looking around, Henry discovers that his bleak world is even more bitter and painful. His comely neighbor has rejected him in favor of another casual lover. She looks disgustedly at Henry as if his head were the head of his "monstrous" baby. His lambkin child still mewls plaintively. Dejected, Henry slumps to the floor. His expression indicates that he is rethinking his wretched existence. He is having his own conversation with Krishna on the field of Kuruksetra.

Henry takes a sharp scissors and cuts away the baby's gauze wrapping which turns out to be more like its skin, since the baby cries in agony as he cuts and then exposes its internal organs. He stabs one of the organs and a doughy substances billows out. The lights in his apartment flicker and go out and furious sparks are emitted from the electrical outlet.

The sparks have been generated by the demonic god who is attempting to regain control of the levers. He frantically pulls and pushes; and as if sharpening steel at a grinding wheel, the sparks fly. He does not succeed. He has been defeated. An aperture appears in a celestial orb which breaks apart, leaving Henry in the arms of his radiator dream girl.

Anyone who thinks that assigning a meaning to this work is a simple matter is kidding himself. Each person will form his own conclusions; and if they help him to deal with the world, the work has succeeded. In Zen terms, Henry lives in the world of Samsara, the world of illusion in which the most bizarre words and deeds seem to acquire an acceptable reality.

A Parallel Universe, the real world of Nirvana, exists beside it but is unattainable for so long as the lines are parallel and, by definition, separate.

Lynch's use of parallel lines is notable. Not since the film Spellbound have so many parallel lines been so mysteriously significant. Worms of various sorts also contribute to the puzzling images.

How does this work reveal its spiritual content? The blonde angelic radiator girl may well represent the ecstasy, solitude, and serenity that is experienced by the person who through the discipline of Jnana Yoga (The Yoga of Knowledge) changes the Path of his life. In any kind of yoga, orgasmic ecstasy is an intricate part of Samadhi, (Divine Union, Tattva #4) which provides the practitioner with all the social and sexual life that he requires - though it certainly does not prohibit him from enjoying family life in all of its aspects. There is a problem, however, with family and friends in that they constantly change and often require the practitioner to dedicate his time to readjusting his relationships and solving the problems these persons create.

An independent spirit informs the life of the person whose parallel samsaric line has been happily erased. The Path to God is always a solitary approach.

In the Mundaka Upanishad we are told that "Like two birds of golden plumage, inseparable companions, the individual self and the Immortal Self are perched on the branches of the self-same tree. The former tastes of the sweet and bitter fruit of the tree; the latter, tasting of neither, calmly observes. The individual self, deluded by forgetfulness of his identity with the Divine Self, bewildered by his ego, grieves and is sad. But when he recognizes the worshipful Lord as his own true Self, and beholds His glory, he grieves no more."

Although the Bible is literally engorged with meaningful lines, any one of which might have been the one that allowed the disparate elements of this strange film to coalesce, we can at least find lines that suggest some of the peculiar images:

In the Book of Job we find comments that resonate with the experiences of Lynch's characters.

"Let the day perish wherein I was born, and the night in which it was said, 'There is a man child conceived.' Let that day be darkness; let not God regard it from above, neither let the light shine upon it."

"So went Satan forth from the presence of the Lord, and smote Job with sore boils from the sole of his foot until his crown.

"Why died I not from the womb? why did I not give up the ghost which I came out of the belly? why did the knees prevent me? or why the breasts that I should suck? For now should I have lain still and been quiet. I should have slept: then had I been at rest."

"Yet man is born into trouble, as the sparks fly upward."

"My flesh is clothed with worms and clods of dust: my skin is broken, and become loathsome."

"When I say, my bed shall comfort me, my couch shall ease my complaint:, then thou scarest me wiih dreams, and terrify me through visions."

"If a man die, shall he live again? All the days of my appointed time will I wait, till my change come."

The question remains: what did Henry do to deserve salvation? What criteria are employed by the Divine to determine who shall be delivered?

In Luke, Chapter 5, we find an answer. "And Levi made him a great feast in his own house: and there was a great company of publicans [pub crawlers] and of others that sat down with them. But their scribes and Pharisees murmured against his disciples, saying, Why do ye eat and drink with publicans and sinners? And Jesus answering said unto them, "They that are whole need not a physician: but they that are sick. I came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance."

Also, the attitude Arjuna is counseled to acquire about life and death in the world of Samsara is also implied with the scissors. We cannot kill that which cannot die. If our duty requires us to dispel the samsaric existence of another, we do it. Particularly if that "other" is part of ourselves, we may not hesitate. Knowledge of the ever-changing material world of illusion is in our brain and it is in our own brain tissue that we can find liberation from the deceits of the world. The roshi or god of the pencils may help us with that.

These are, of course, the attitudes of Zen. Whether we have succeeded or blundered in our responses in the world of illusion, the right or wrong of them is gone in a flash when we experience our moment of enlightenment.

So Henry abandons the illusionary world. The line of his former path has been eradicated. He has his good things and he has his Anima's good things. He is complete. She is in his arms, and the aims of the demonic god who had formerly controlled his fate have been thwarted.

In Zen we understand that we can never really see ourselves, that we cannot be our own judge, jury, prosecutor, and defense attorney. If we are discontented with our existence, if we are beset by social or political issues, if we are jealous, angry, or proud, we cannot waste our time trying to cause trouble for those we believe are troubling us, or even worrying about things that are as worthless as so much eraser dust. We can only say with some confusion, "I am not the man I was when I was twenty - but neither am I anyone else."

And then, if we are fortunate enough to have the truth drilled into our cerebral cortex, we will find our true nature.... The serene One who calmly observes.