Home » Literature Archives » REMEMBERING DAVID CARRADINE

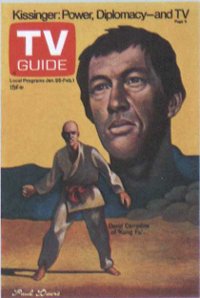

REMEMBERING DAVID CARRADINE

By Ming Zhen Shakya

My horse suddenly stumbled

Just outside the house.

-- Buson

David Carriadine has died. We mark his passing here because he, more than any other man, can be credited with bringing the Chan of Mainland China to the west.

He did not intend to do this. He was an actor and his only mission was to create a unique but believable character: Kwai Chang Caine, a gentle, solitary man of Chinese-American descent who was searching for his brother in the American West of the late l800s.

The character, Caine, had grown up in China, in the Shaolin Monastery in Henan Province. He had mastered the martial arts and doubtlessly would have stayed on at Shaolinji as a Buddhist monk had the Emperor's nephew not killed his beloved mentor, old, blind Master Po. In retaliation, Caine killed the young royal, an act which forced him to flee from China and allowed him to begin searching for his American relatives. Regular flashbacks revealed his "Grasshopper" childhood and adolescent life in China.

Initially, the announcement that David Carradine would be cast in the leading role of Kung Fu was met with amused consternation. As presented, Kwai Chang Caine was an adept in the martial arts and David Carradine not only knew nothing about Gong Fu or any of the martial arts, but he could not even sit in an ordinary lotus posture. Caine was bi-racial; and Carradine was a Caucasian of mostly west European ancestry. There was nothing remotely Asian about him. Complicating matters, Bruce Lee claimed that he had created the concept and presented it to several studios, intending himself as the lead character. Regardless of the extent of his contribution to the project, the producers felt that during those Viet Nam years an American audience would not be receptive to someone so oriental as Lee. Further, they preferred the lead character to have a more sensitive persona and a competence in acting that exceeded Lee's abilities. They felt that since martial arts films were all carefully choreographed, only an ability to dance was essential. Carradine, while not an accomplished ballet dancer, could dance well enough to perform the movements, but that was all there was on the plus side. No one gave the TV series much of a chance.

But Carradine's extraordinary demeanor, the convincing, spiritual gentleness he brought to the role obliterated all the negatives. He created the impossible: a peaceful man who carried no weapons and yet was the consummate warrior: a humble man who was bereft of material comforts and yet possessed an indomitable mind that could always sustain him. Carradine had vivified Everyman's pallid image of the self-reliant, itinerant Buddhist monk.

The series, which ran for three years - 1972-75, was shown around the world - everywhere, it seemed, except China. And wherever it was shown, people quite literally adored the series. The charm of Master Po's mentoring of his young pupil; the wisdom of Master Kan; and Kwai Chang Caine's serene disposition, his sense of fairness, and his pacifistic response to conflict, combined to put China and the U.S. together in a favorable light. Martial arts' studios, advertised as teachers of "Shao Lin style Kung Fu," sprang up all over the U.S. and, we can safely suppose, in any country in which the series was shown.

The astonishing extent to which a non-political individual can influence world politics had just been demonstrated in 1971 when Japan hosted an international table tennis competition and both the U.S. and Chinese teams participated. At the end of an out of town practice session, American Glenn Cowan missed his team's return bus. Stuck, he looked around and saw a player on the Chinese bus gesture that he could go back with them. World Champion Zhuang Zedong gave the likable American a souvenir gift and by the time the bus ride ended, Ping Pong Diplomacy had been initiated.

At the time, there were no diplomatic relations between the U.S. and China - and there had not been any for nearly a quarter century. In fact, there was nothing but mutual contempt. China was virtually closed to the world, and such news as came from that beleaguered country was all bad. The Red Guards' Cultural Revolution had closed its universities, killed or imprisoned its intellectuals, artists, and clerics of every kind, and destroyed many of its churches and temples. Zhou EnLai was striving to get the country to return to sanity. Zhou EnLai invited the U.S. team to visit China.

Richard Nixon approved the team visit and ordered Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to begin the long and complicated process of re-establishing formal relations with mainland China.

By 1979 it was possible to travel to China, and from all over the world people came to see the Shaolin Temple where Kwai Chang Caine had grown up. The TV series had used an old, revamped Camelot set for filming the temple scenes and tourists wanted to visit that stone, sort-of-Gothic temple. Unfortunately, Shaolinji had been destroyed by the Red Guards in the course of their Little Red Book fanaticism. Only one of its old buildings remained, and this building was rather shabby. China's new tourist agency made it their business to accommodate the tourists.

In 1982 I joined the congregation of a small local Taiwan Chinese temple and helped several of the nuns to study for their citizenship tests. I also taught them some of the esoterica of advanced Zen, topics that are not ordinarily discussed with women in China. In l984 I went to Taiwan and began to teach and to study (the master had a great English library) at their monastery. After a semester, I flew to Hong Kong and in the People's Republic of China's tourist office I was specifically asked by the agent if the monastery I wanted to visit was Shaolinji. Puzzled, I said I was a follower of the Sixth Patriarch and was interested only in Nan Hua Temple in Guangdong Province.

When I arrived there, I learned how enormous the impact of David Carradine had been. The road to Nan Hua was still an old, long dirt road which led to the dilapidated wooden temple gates. But, I was told, work was continuing at the reconstructed ShaolinJi. Thousands of tourists were making "pilgrimages" wanting to see the place that the TV show had made famous. Fortunately, the tourists were also interested in seeing some of the great Chan Buddhist Monasteries - among them the little cluster of ancient temples around Shao Guan: Nan Hua, Yun Men, and the exquisite Danxia Shan. Quickly the roads were paved and the buildings renovated or replaced. Hotels for tourists were constructed close to all the great Buddhist temples; and from everywhere on the planet, people came to experience Chinese Chan.

And naturally, Chinese Chan was also exported. In the l980s I became the first American to be fully ordained in China since the revolution; and in every one of the four times I went to China to visit Nan Hua Temple (where I was ordained) I was invariably asked many questions about the half-American, half-Chinese Buddhist martial artist monk - who had now become a legend. The curiosity he generated cannot be underestimated. I'm told that the series was broadcast from Hong Kong and even on state channels inside China. There is no doubt in my mind that, as regards my ministry, I am personally indebted to David Carradine and his indelible portrait of a gentle warrior, the quintessential Buddhist.

But what are we to say about his later years and his death? First, he knew how people conflate the actor's character with that of the role he is playing. Many actors play doctors so convincingly that people will often ask them for medical advice; but none that I know of has subsequently gone to medical school. Carradine did take the trouble to learn martial arts. He also learned tai ji quan and, even considering his age as a beginner, he did the exercise gracefully. He continued his film career, giving exemplary performances in Bound for Glory and Kill Bill. He had a generous nature, and it was totally in character for him to offer his instructional tai ji quan disks to public television stations for them to use in fund raising drives. He even appeared in person on their shows. The manager of the hotel in Thailand in which he died remarked that Carradine would entertain the guests in the lobby by playing the piano or the flute.

And his death by auto-erotic asphyxiation? It was neither sordid nor shameful. He was a human being and he was alone in a hotel room far from home. When it comes to things sexual, a man alone, who is exploiting no one, is keeping his own affair. It is not for us to decide what is acceptable and what is not.

Was the practice foolish because it is so inherently dangerous? Yes. It is unfortunate that the element of danger often adds to its attraction. Perhaps if it were discussed more openly and intelligently - without demonizing it or sanctifying it as was recently done on the Science Channel's Mystery of the Tibetan Mummy - fewer people would subject themselves to its risks. People simply do not realize how quickly a person can become unconscious when the brain is deprived of blood. Police and martial arts' choke-holds are not lethal because they prevent breathing: they are lethal because they stop the flow of blood to the brain. When I was a kid, as something funny to do to each other, we would apply strong thumb pressure to either side of the trachea. In less than a minute we'd pass into unconsciousness. A garrote's compressive force is distributed around the entire neck, and while this is admittedly less efficient, under the peculiar delirium of an erotic fantasy, it lingers long enough to do a permanent job. The death rate is invariably underreported. In consideration of a family's embarrassment and grief, the cause of death is often attributed simply to accidental choking.

In Carradine's case, however, there is an especially poignant element to his sad death. Had he only learned the esoteric disciplines of Zen, he would have accessed the pleasure centers of his own brain and experienced the indescribable ecstasy of Divine Union - a state which makes experiences achieved with the little tricks of ropes and ribbons seem quaint and childish. Had he practiced even rudimentary but true forms of meditation, the Healing Breath alone would have would have slowed his breathing down to a point of imperceptibility and he would have often known that long eternal moment of bliss that he strove so pathetically to achieve. David Carradine had done much for Buddhism. What awful fate blocked him from entering into its mysterious refuge?

Samuel Beckett, who happened to be one of the few authors who ever referred to erotic asphyxiation, has Pozzo, in Waiting For Godot, describe to Estragon and Vladimir the fading event of daylight. "...it begins to lose its effulgence, to grow pale... pale, ever a little paler, a little paler until - pppfff! finished! - it comes to rest. But.. but.. behind this veil of gentleness and peace night is charging and will burst upon us (he snaps his fingers) pop! like that! - just when we least expect it. That's how it is on this bitch of an earth."

Rest in peace, David Carradine. Your wait for God is over.